Livestock mitigation- Mario Herrero – Nov 2012 from CCAFS | CGIAR program – Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security

‘Fewer but better fed animals can make livestock production more efficient.’ This was said by Mario Herrero at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) in Nairobi. Herrero was speaking on 13 November 2012 in the fourth of a series of science seminars organized by the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food security (CCAFS). The presentation was live-streamed to an online audience of 220 people.

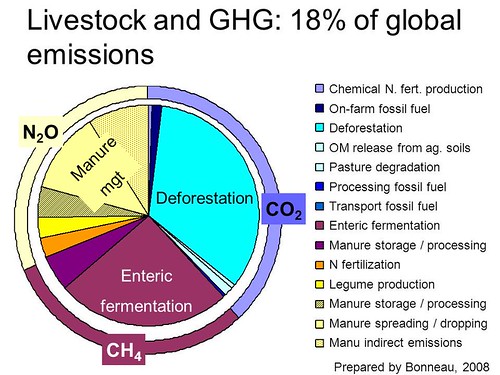

Herrero, an agricultural systems analyst at ILRI, gave an up-to-date overview of ways the livestock sector in developing countries can help mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, which are causing global warming. `We face the challenge of feeding an increasing human population, estimated to reach 9 billion by 2050, and doing so in ways that are socially just, economically profitable and environmental friendly,’ he said.

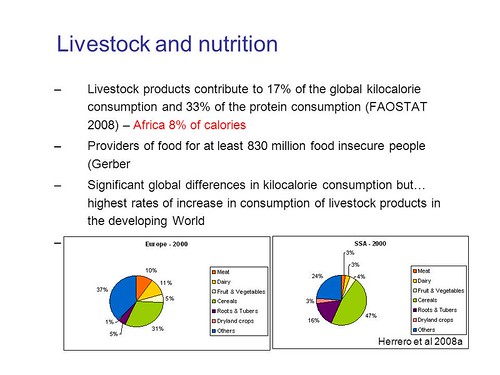

This matters a lot. There are about 17 billion domestic animals in the world, with most of these in developing countries. The raising of these animals generates greenhouse gases such as methane (emitted through enteric fermentation and some manure management practices). And the number of livestock in the developing world will only increase in future decades.

Livestock benefit many of the world’s poorest people, with at least 1 billion of them depending either directly or indirectly on livestock for nourishment and income and livelihoods. But most of the inefficiencies in livestock production occur in developing countries, where people lack the resources to refine their production practices.

The good news is that livestock production in poor countries can be improved dramatically to close big yield gaps there. Herrero gave some examples:

- Discourage and reduce over-consumption of animal-source foods in communities where this occurs,

- Encourage and provide incentives to small-scale farmers to keep fewer but better fed and higher producing animals, and

- Promote ways of managing manure from domestic animals that reduce methane emissions.

Herrero leads ILRI’s climate change research and a Sustainable Livestock Futures group, which reviews interactions between livestock systems, poverty and the environment. He says, `In the coming decades, the livestock sector will require as much grain as people. That’s why there’s great need to keep fewer but more productive farm animals. We need to find ways to produce enough food for the world’s growing human population while reducing global warming and sustaining livelihoods of the poor.’

That, says Herrero, will involve some hard thinking about hard trade-offs.

For instance, while reducing the number of animals kept by poor food producers, and intensifying livestock production systems, could reduce global methane emissions by livestock, we’ll have to find efficient and sustainable ways for small-scale farmers and herders to better feed their animal stock. And while raising pigs and poultry generates lower levels of greenhouse gas emissions than raising cattle and other ruminant animals, pigs and poultry cannot, like ruminants, convert grass to meat.

‘There’s no single option that’s best,’ cautions Herrero. ‘Any solution will need to meet a triple bottom line: building livelihoods while feeding more people and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.’

Click on this link to view Mario Herrero’s full presentation: Mitigation potentials of the livestock sector,http://www.slideshare.net/cgiarclimate/livestock-mitigation-mario-herrero-nov-2012